Preserving wild places may require more human intervention. This somewhat counter intuitive statement is the thrust of an opinion article in the New York Times by Christopher Solomon a few days ago (click here to read the article). The article is a discussion about how the Wilderness Act is facing some changes in the new world of climate change. It puts forth some interesting facts about the challenges wilderness areas are facing and some ideas about how human intervention may be needed to preserve wilderness areas. We recommend everyone concerned with open space preservation take a look.

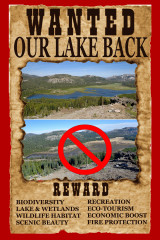

While the Donner Summit Valley would not technically be considered a wilderness area, as an open space area it does face many of the problems that are discussed in the article. Human intervention has had both good and bad effects in the valley. Intense logging of the valley changed the old growth red fir and white pine forests to predominantly thick lodgepole forests. Years of sheep and cattle grazing took it’s toll on the valley right up until the 1950’s. The presence of a large PG&E storage lake covered half the meadow in water for over 100 years. Fortunately, in the last 40-50 years the valley has pretty much been left on its own and nature as the consummate environmentalist has established a thriving blend of lake, wetlands, riparian and meadow habitats that make it an oasis of biodiversity in the Sierras. As a bendficial affect of human intervention, the addition of added water storage in the valley as a result of the residual Van Norden Dam is responsible for offsetting many of the negative affects of past exploitation of the valley.

There is a segment of the wilderness article that is particularly relevant to a threat that the Summit Valley faces today. I include here that paragraph

Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park is one of the most arresting places in the West, and it’s important as the largest subalpine meadow in the Sierra Nevada.

But as the climate changes, the meadows, some of which lie in the Yosemite Wilderness, are being invaded by lodgepole pine. Keeping the meadows intact will require regular tree-cutting and possibly irrigation for species intolerant of drier conditions, according to David Cole, an emeritus scientist with the Forest Service’s Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute and co-editor of “Beyond Naturalness,” a 2010 book of scholarly essays about wilderness and climate change.

That’s right, they may have to irrigate Tuolumne Meadows to keep it a meadow the Lodgepoles out.

Anyone that has been out in the Summit Valley knows that there is an active invasion of Lodgepole pines going on. Before 1976 when the dam was breached to create the current lake, the large 5800 acre-ft lake prevented the Lodgepoles from coming into the valley. But when the lake was reduced to its current size, the Lodgepoles (which can grow at a density of 1000 trees per acre) took advantage of the drier meadow and the invasion was on. The encroachment of Lodgepoles can clearly be seen in Figure 1 in which satellite maps from 1979 and 2012 show the results of the invasion. In those 38 years dense thickets of trees have sprung up and started marching out into the valley until they hit the surface water table of the lake and wetlands. Without the lake and wetlands there will be nothing to stop the march of the Lodgepoles out into the meadow, just like what is occurring in Tuolumne Meadows as they dry out. In drought years such as this there will be dense stands of dry Lodgepoles. A perfect target for wildfires. This is yet another of the detrimental effects that the draining of the lake and wetlands will have on the Summit Valley. Keeping the meadow opened would require a continuous tree cutting program by its stewards (the Land Trust and the Forest Service). And how crazy would it be if the lake and wetlands were drained and then eventually the valley had to irrigated to help prevent encroachment and support meadow vegetation.

Anyone that has been out in the Summit Valley knows that there is an active invasion of Lodgepole pines going on. Before 1976 when the dam was breached to create the current lake, the large 5800 acre-ft lake prevented the Lodgepoles from coming into the valley. But when the lake was reduced to its current size, the Lodgepoles (which can grow at a density of 1000 trees per acre) took advantage of the drier meadow and the invasion was on. The encroachment of Lodgepoles can clearly be seen in Figure 1 in which satellite maps from 1979 and 2012 show the results of the invasion. In those 38 years dense thickets of trees have sprung up and started marching out into the valley until they hit the surface water table of the lake and wetlands. Without the lake and wetlands there will be nothing to stop the march of the Lodgepoles out into the meadow, just like what is occurring in Tuolumne Meadows as they dry out. In drought years such as this there will be dense stands of dry Lodgepoles. A perfect target for wildfires. This is yet another of the detrimental effects that the draining of the lake and wetlands will have on the Summit Valley. Keeping the meadow opened would require a continuous tree cutting program by its stewards (the Land Trust and the Forest Service). And how crazy would it be if the lake and wetlands were drained and then eventually the valley had to irrigated to help prevent encroachment and support meadow vegetation.

Reiterating the theme of increased water storage that we made in the last post, it seems that the human intervention that created the current lake bolsters the premise made in the New York Times article. In many situations, the hand of man can greatly enhance the natural processes to create a richer, more verdant ecosystem.