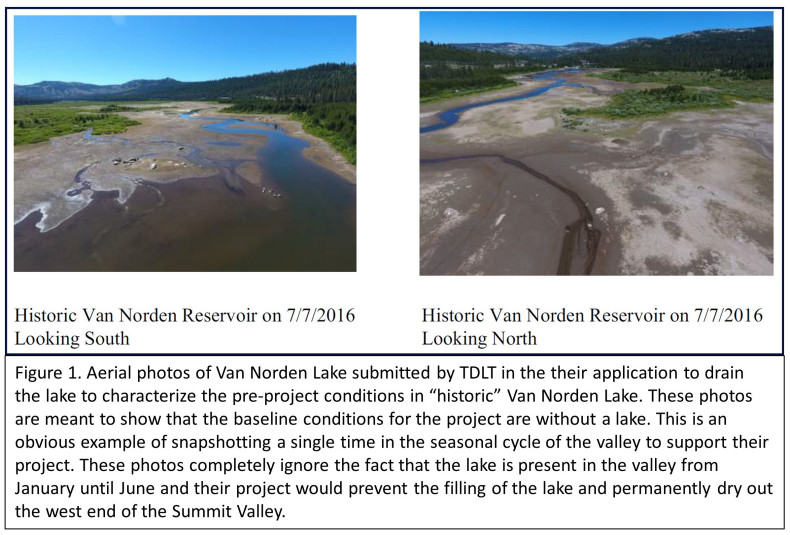

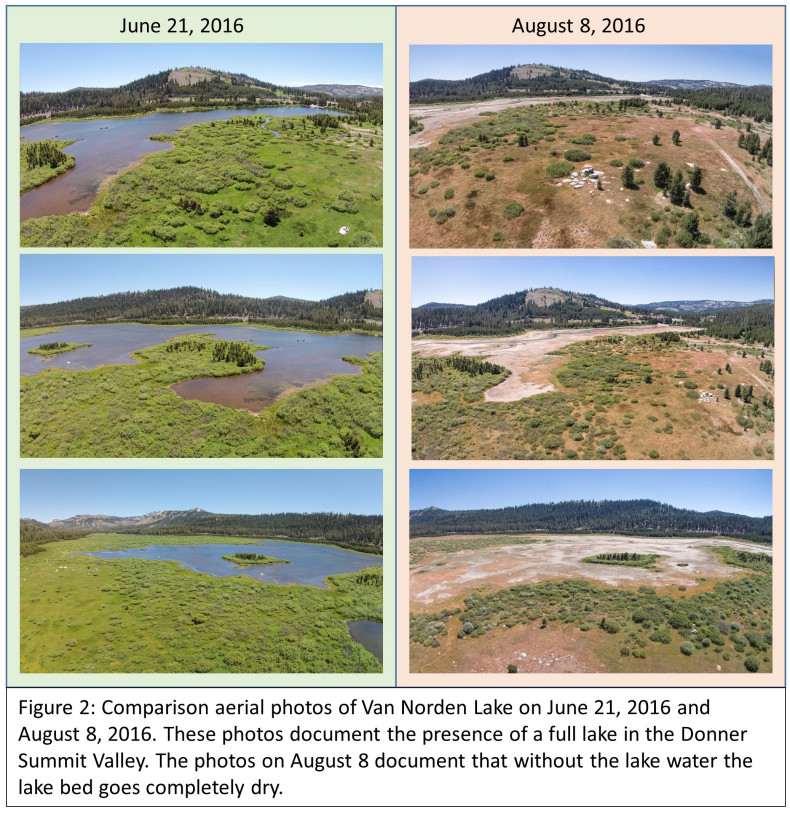

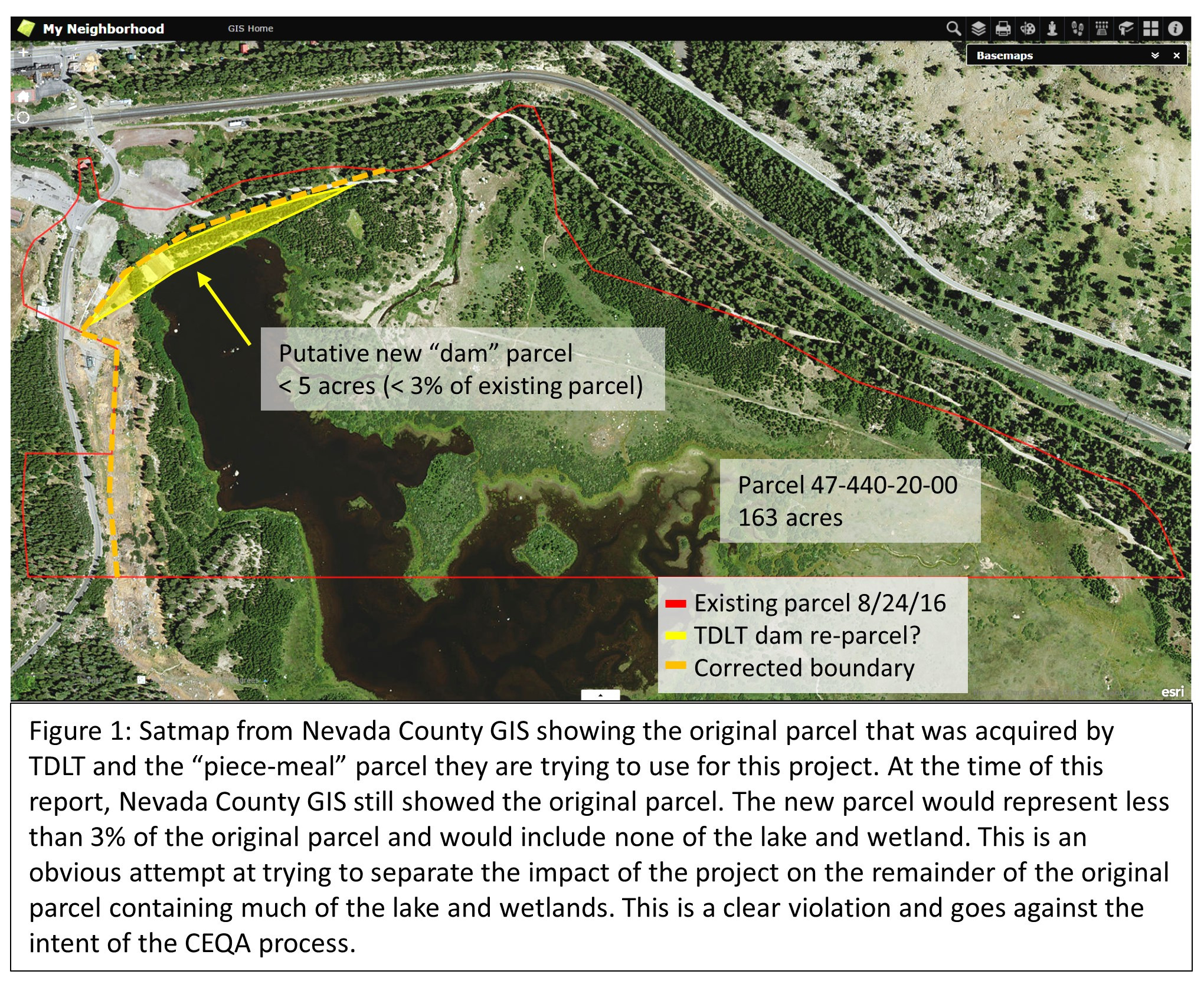

This counter-intuitive claim is one that the Truckee Donner Land Trust has been making ever since they were pressured by the US Forest Service to drain the lake. This claim is a perfect example of misdirection using concepts and data for meadow restoration that are not really applicable to the Donner Summit Valley.

The Claim

The claim is that after the 180 acre-ft of water currently stored in the 70 acre Van Norden Lake is drained and the meadow is “restored”, there will be more water stored in the Donner Summit Valley. If you are scratching your head at this one, you’re not alone. The Land Trust and SYRCL are making this claim based on the results of other meadow restoration projects that really don’t equate with the situation in the Summit Valley. The claim is based on a distortion of the very simplistic concept of a meadow acting as a “sponge” to store ground water.

The Reality

As with many things in nature the reality of water storage in the Donner Summit Valley is more complicated than simplistic models. In order to understand why this claim is false requires that we spend a little time looking at some hydrology and delving into the nature of meadows in the Sierras. For a pretty thorough discussion of meadow architecture and restoration in the Sierras you should take some time to read the following master’s thesis by Adam McMahon.

Meadows are pretty special places in the Sierras. While they are formed in the wider, flatter glacially formed canyons and valleys of the mountainous watersheds of the Sierras, the status of each meadow is ultimately determined by the way in which water falling on the mountains in form or rain and snow interacts with the meadow area, its hydrology. Not surprisingly the hydrology of a meadow is dependent on many factors, both natural and man-made. The amount of precipitation, the form of precipitation (rain or snow), the geology and soil makeup of the area, the elevation of the meadow, and the human activity in the area all influence the condition of a meadow. This is especially true for the Donner Summit Valley.

Where does the water come from and where does it go

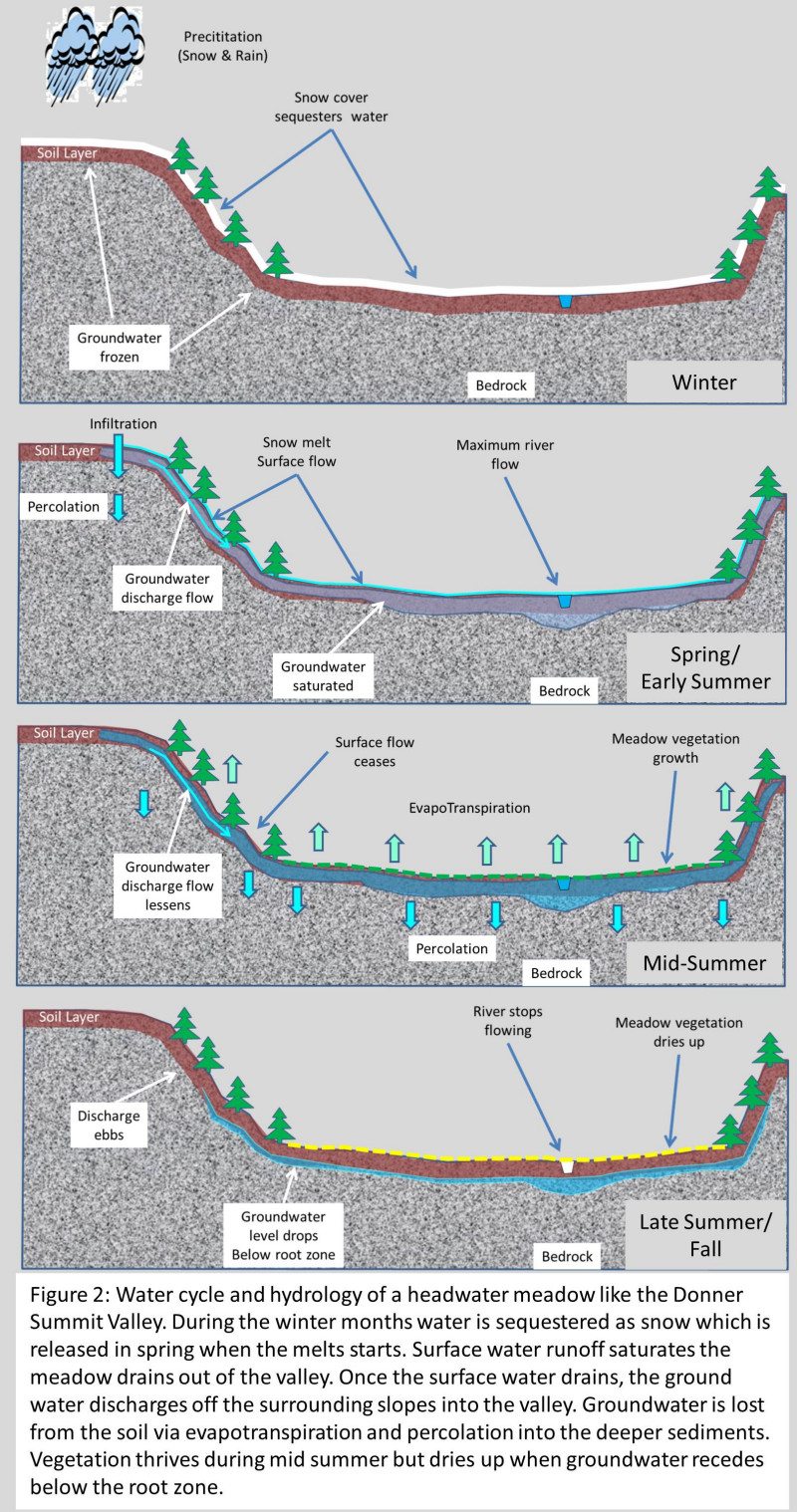

In order to understand the hydrology of a meadow it is necessary to understand where the water comes from. In the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California the water cycle is pretty well defined. Pacific storms during the winter months from November to April drop tremendous amounts of rain on the foothills of the Sierras and snow on the mountains themselves. During the summer months there is very little precipitation and the warmer summer temperatures dry out the soil and melt the snow which drains off of the mountains. Most of the water falling in the high mountains drains down to the Central Valley via the myriad of creeks, stream and rivers that have carved out the vast network canyons and valleys on the west side of the Sierras.

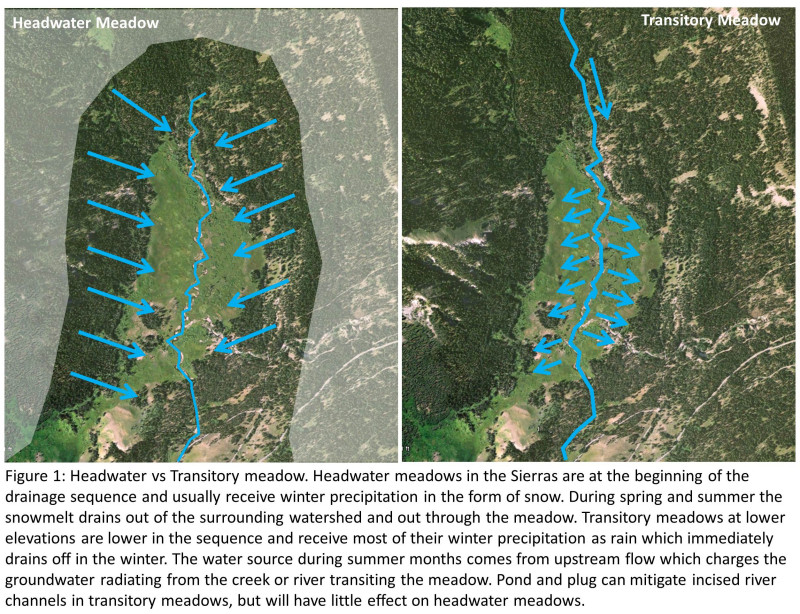

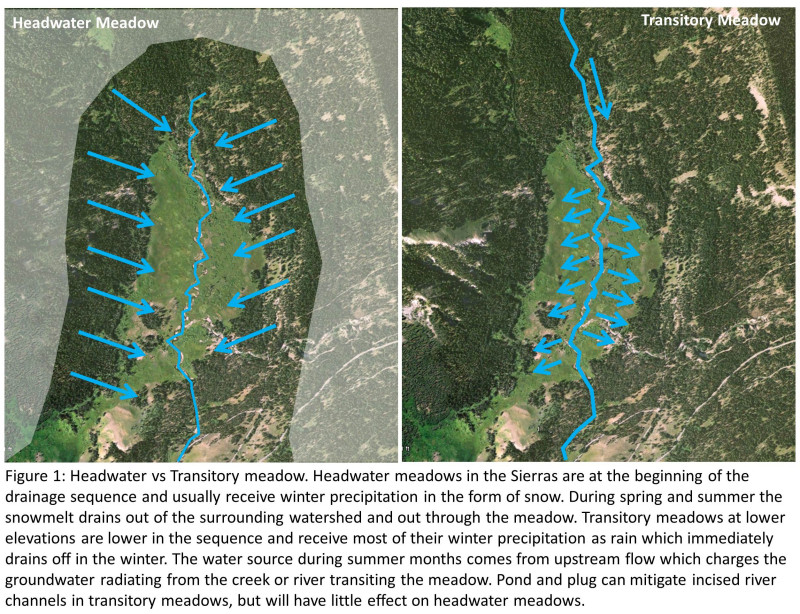

The hydrology for every Sierra meadow is dependent upon this cycle. However, the source of the water for a meadow in the Sierra is primarily dependent upon where it sits in the drainage sequence. Meadows can be characterized by their location as either a headwater meadows that is at the crest of the drainage and directly at the source of water (snow) or a transitory meadow which is lower in the drainage sequence and the water transits through on its way down the drainage slope. The number of headwater meadows is relatively small since the crest of the drainage slope is a small portion of the total area of the Sierras. Transitory meadows are much more prevalent.

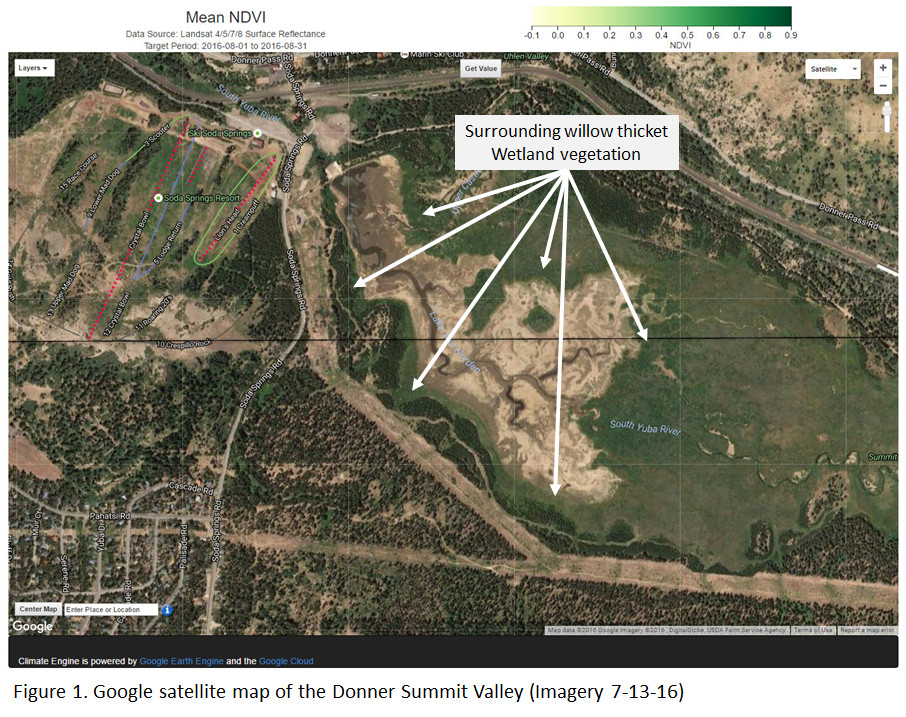

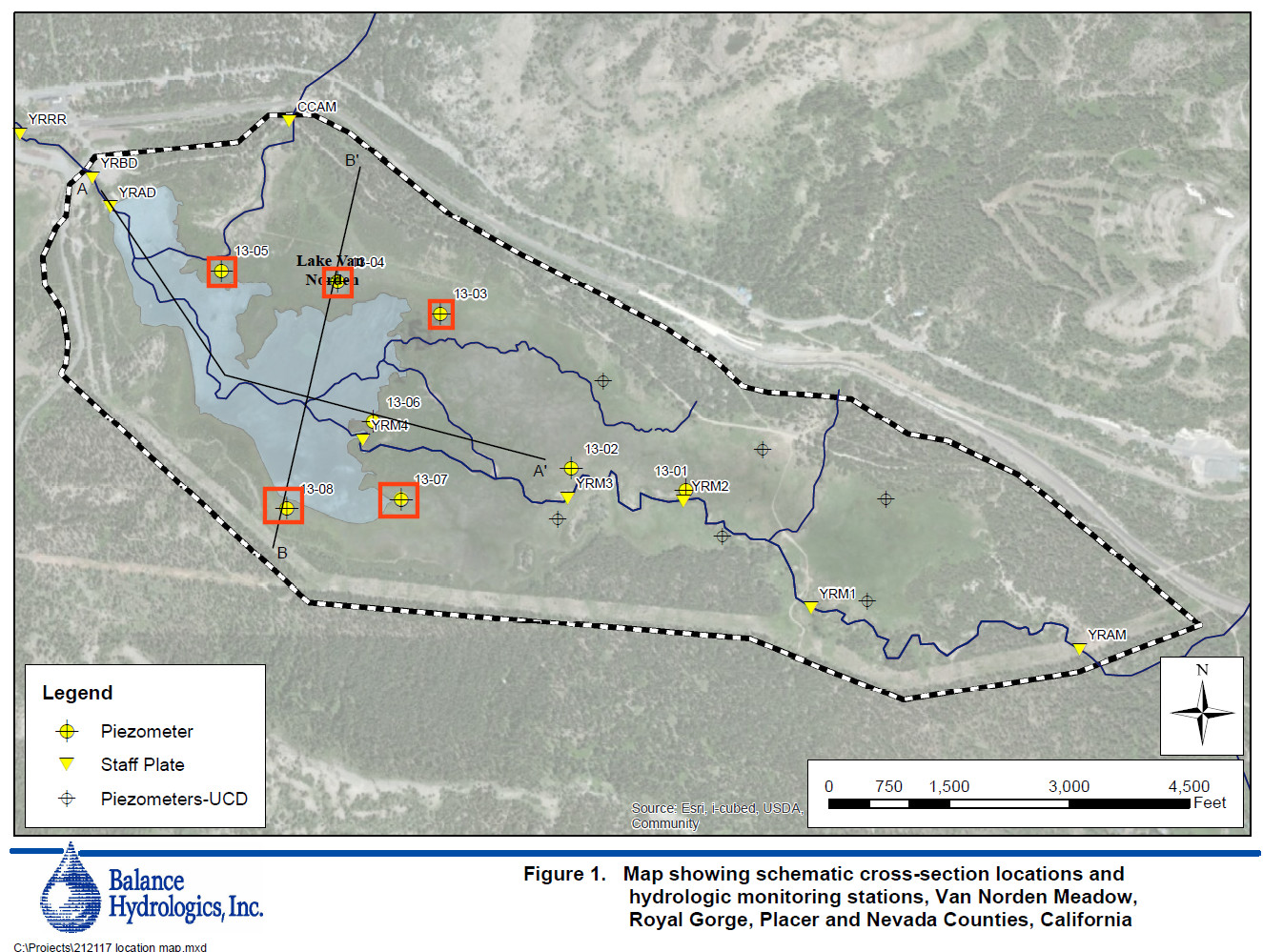

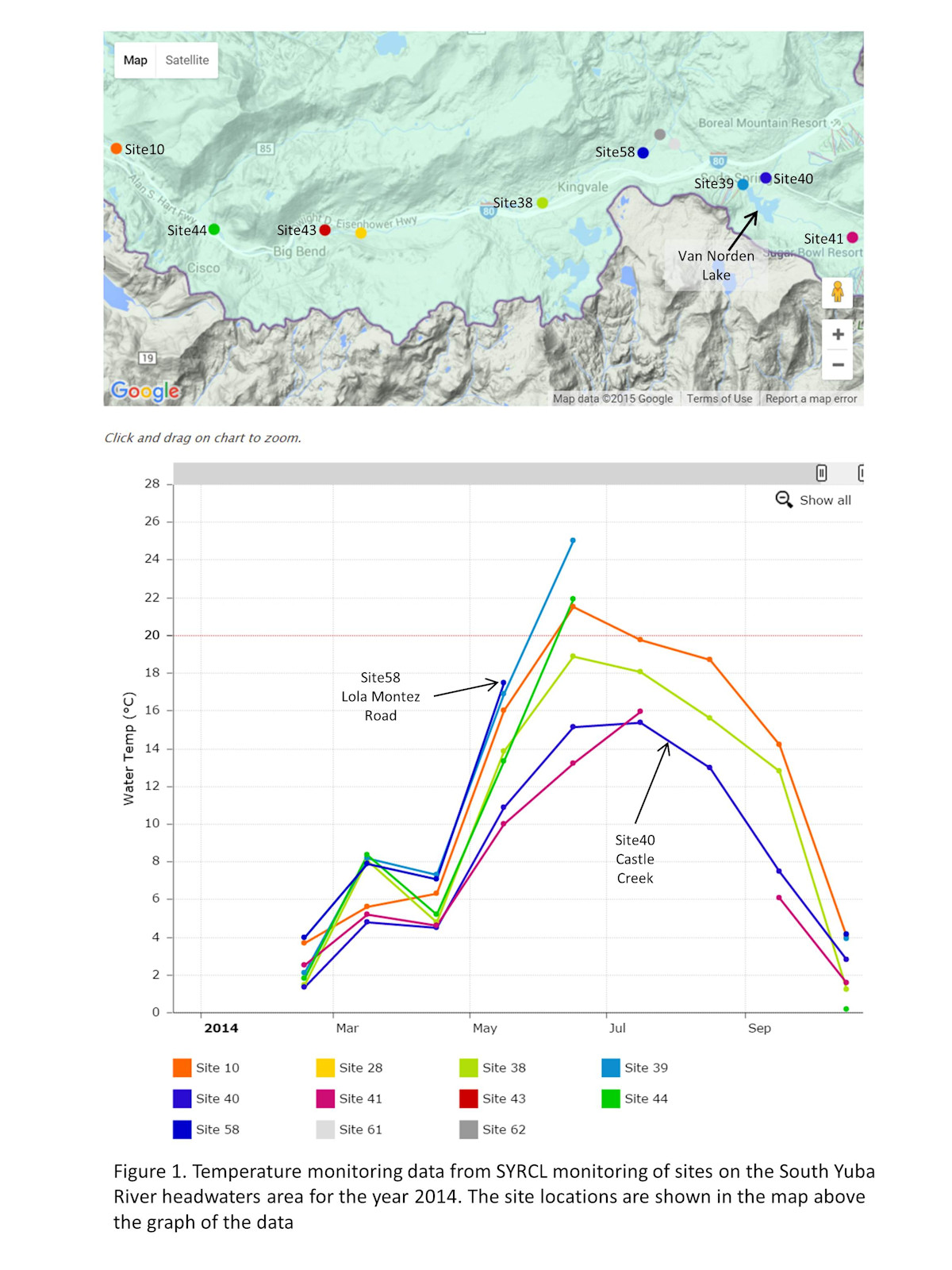

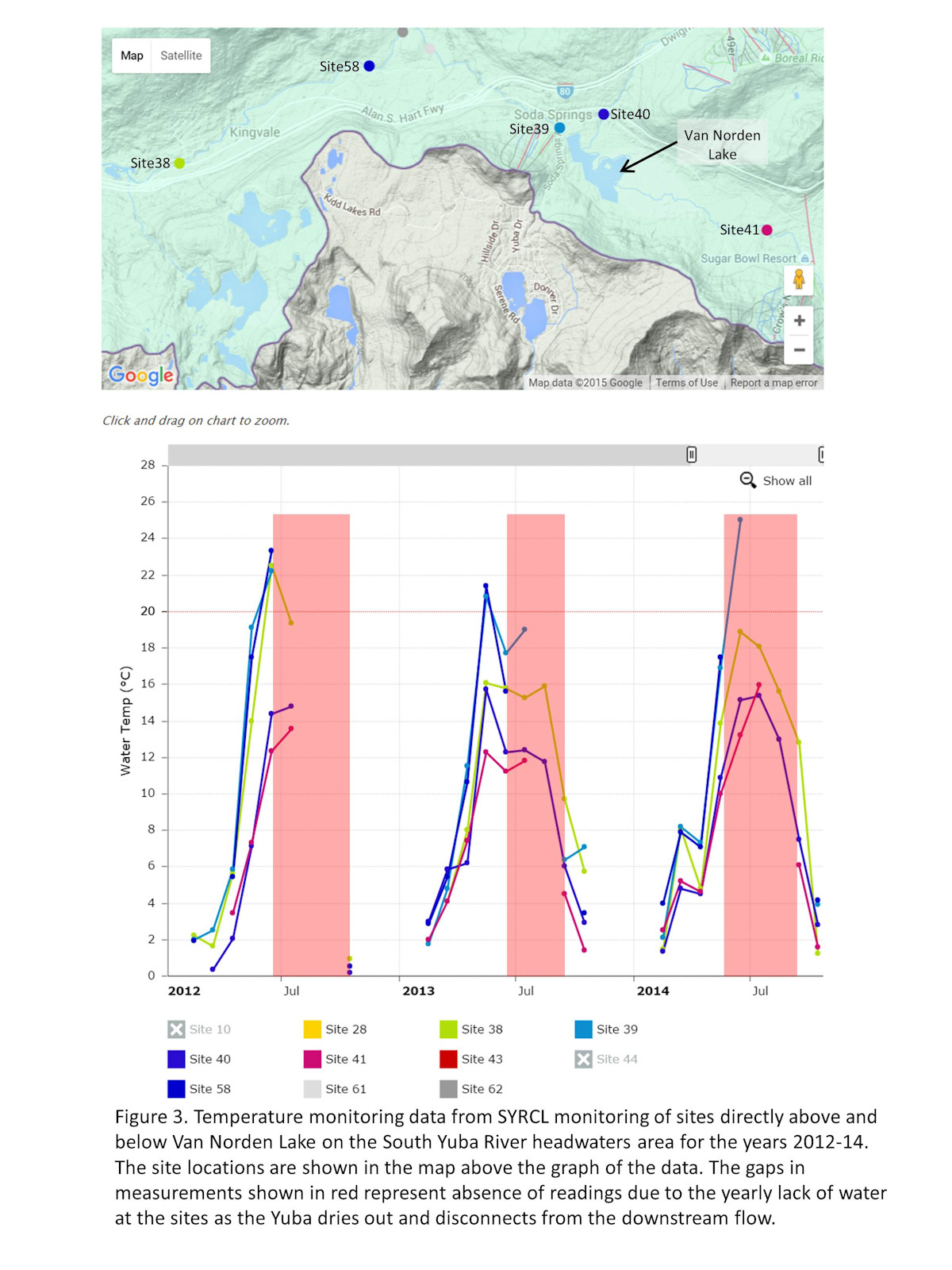

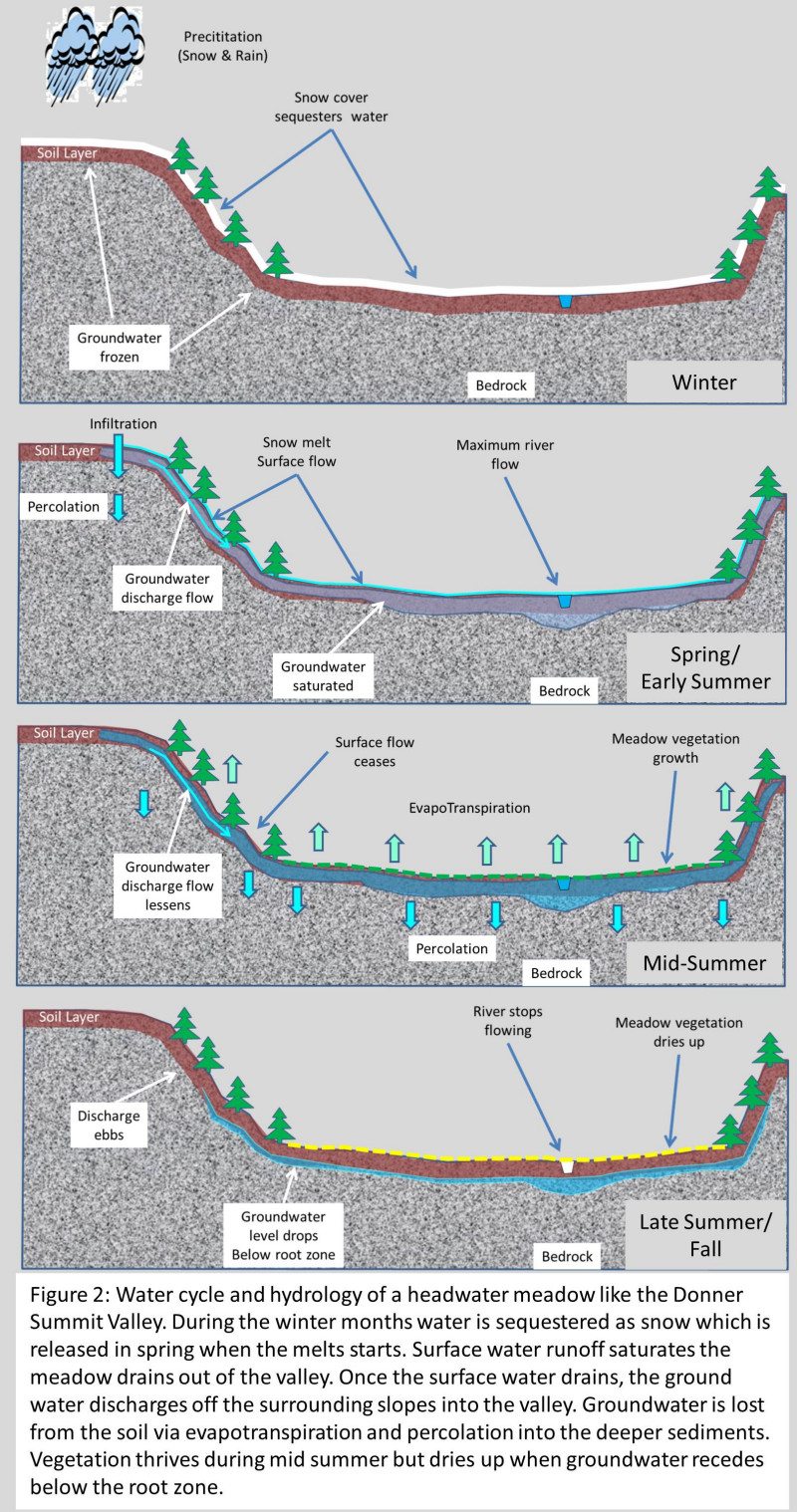

As you might expect the hydrology is quite different for these two types of meadow. That difference is illustrated in Figure 1. A headwater meadow such as the Summit Valley (see Figure 2) at the crest of the Sierras will normally be inundated with snow during the winter which sequesters the water during the winter months. It is not until the spring and summer months that the water is released by the melt and drains out of the meadow. Once the melt water drains from the meadow usually by mid-summer, there is no additional input of water until the winter snows come again. Transitory meadows that are lower in the drainage sequence will receive most of winter precipitation in the form of rain which will quickly drain off. However, they will also receive water during the summer in the form of winter runoff from melting snow at higher elevations. That water usually transits through the meadow in a river or creek bed.

Meadow Restoration

Most of the hype you will hear about meadow restoration has to do with modifying the drainage through a meadow. The popular method of doing this currently is a modification called “pond and plug” (or plug and pond). The concept behind this method is pretty simple. As water drains though a meadow it usually erodes out a channel at the low point forming a creek or river. The South Yuba River running through the Summit Valley is a perfect example. If the velocities of water flow are high like the heavy rains and snowmelt in the valley are prone to be, eventually the river bed cuts a channel below the flood plain of the meadow. When this happens the river is said to disconnect the water drainage from the flat floodplain of the meadow. This is what has come to be known as a “degraded” meadow and is the plight of many transitory meadows in the Sierras. While this erosional cutting down of the river banks is a natural process, it can be exacerbated in many meadows by human activities such as stock grazing, logging and recreational facilities such as ski resorts.

The obvious fix for a disconnected channel is to simply fill in the channel so that the water entering a transitory meadow will spread out over the flood plain again. This is really throwing a meadow back in time to a previous state before the erosion process has done its work. Not only can this be prohibitively expensive, but it is only a matter of time before erosion will re-cut the channel.

A modification of the fill in process was developed in the 1990s by David Rosgen, a hydrologist working for the Forest Service. He came up with a system of excavating short hardened plugs in an incised river channel. The plugs act as small dams that form a series of ponds along the river channel. When the spring melt waters enter a meadow the plugs force the ponds to overtop the channel banks and the water sheets out into the floodplain of the meadow. This method has been employed in many transitory meadows in many watersheds in the west over the last 20 years with varying degrees of success. While this method is not really natural (it does not really occur anywhere naturally in the Sierras) it has improved the state of many transitory meadows.

Donner Summit Valley is a headwater meadow – a double edged sword

When people say that the Donner Summit Valley and Van Norden meadow are “special” places, it is not just rhetoric. The Donner Summit Valley is uniquely situated right at the Sierra crest and as such is a prototypical headwater meadow. The area receives 34 ft of snowfall on average making it one of the highest snowfall areas in the lower 48. This makes the hydrology of the Summit Valley very special and is the primary reason why the meadow thrives. And getting back to water storage, it is the reason that once Van Norden Lake is removed there will be much less water stored in the valley.

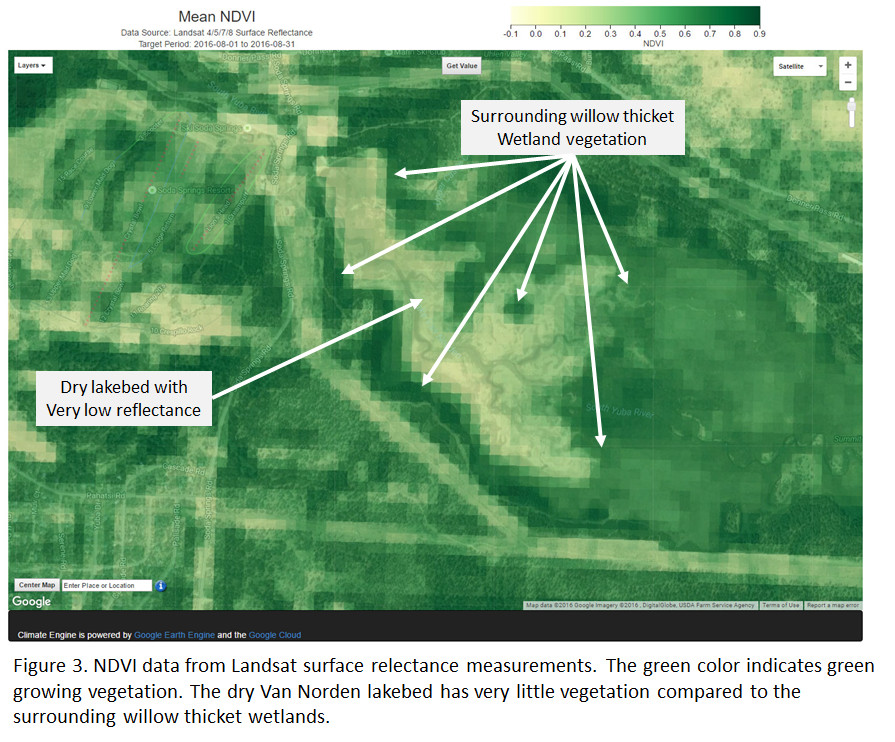

Unlike a transitory meadow, a headwater meadow like the Summit Valley is high at the source of the drainage sequence. While that means that it has a direct source of water from the accumulated snow, once it melts in spring and early summer and drains out of the valley, there is no more water coming down from upstream as in a transitory meadow. It also means that the unlike a transitory meadow where the input of water into the meadow comes from a river or creek upstream of the meadow, the water flow in a headwater meadow is one way drainage out of the meadow and down the drainage system, the South Yuba River in the case of the Summit Valley as shown in Figure 3. While the water is melting in the meadow and on the surrounding mountains there is a constant flow of surface water draining into the meadow which keeps the ground water saturated. Just walk out in the Summit Valley in May or June but be sure to wear your Welles because there is a sheet of 2-4 inches of surface water on the meadow. However, by the middle of July the surface water has drained out of the valley leaving only subterranean ground water.

Coup de Grass

Please excuse the pun here. By mid July the surface water has pretty much drained away leaving only the ground water in the valley. At this point we can use the “sponge” metaphor and say that the meadow is fully charged with water. However, according to the sponge metaphor, this would be the time when the ground water would be helping to maintain the flow of the Yuba River by seeping back into the river channel. This is where the sponge metaphor falls apart.

Please excuse the pun here. By mid July the surface water has pretty much drained away leaving only the ground water in the valley. At this point we can use the “sponge” metaphor and say that the meadow is fully charged with water. However, according to the sponge metaphor, this would be the time when the ground water would be helping to maintain the flow of the Yuba River by seeping back into the river channel. This is where the sponge metaphor falls apart.

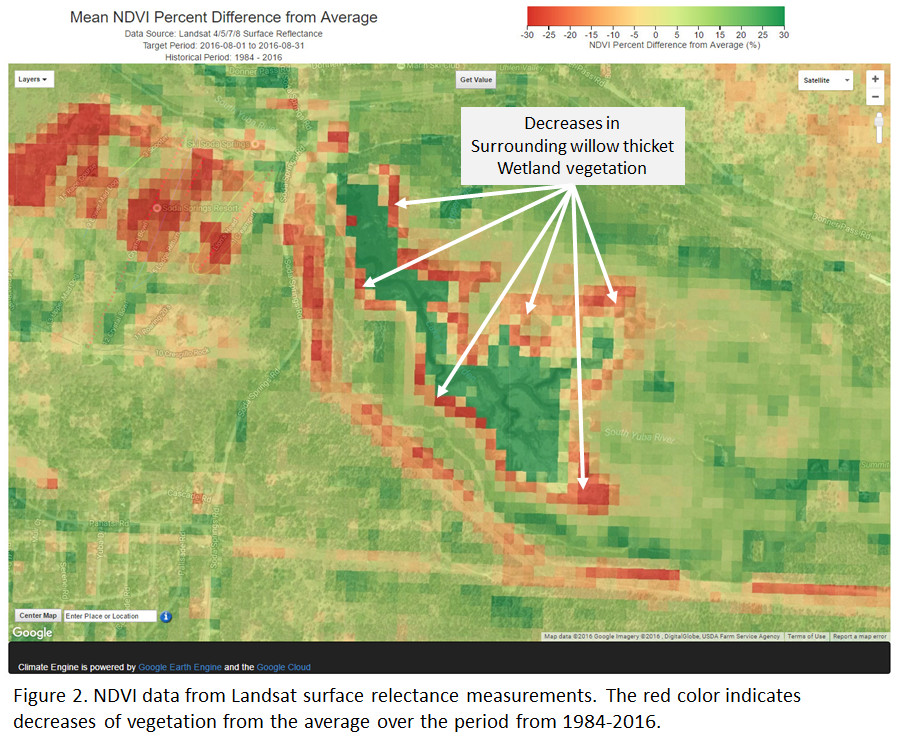

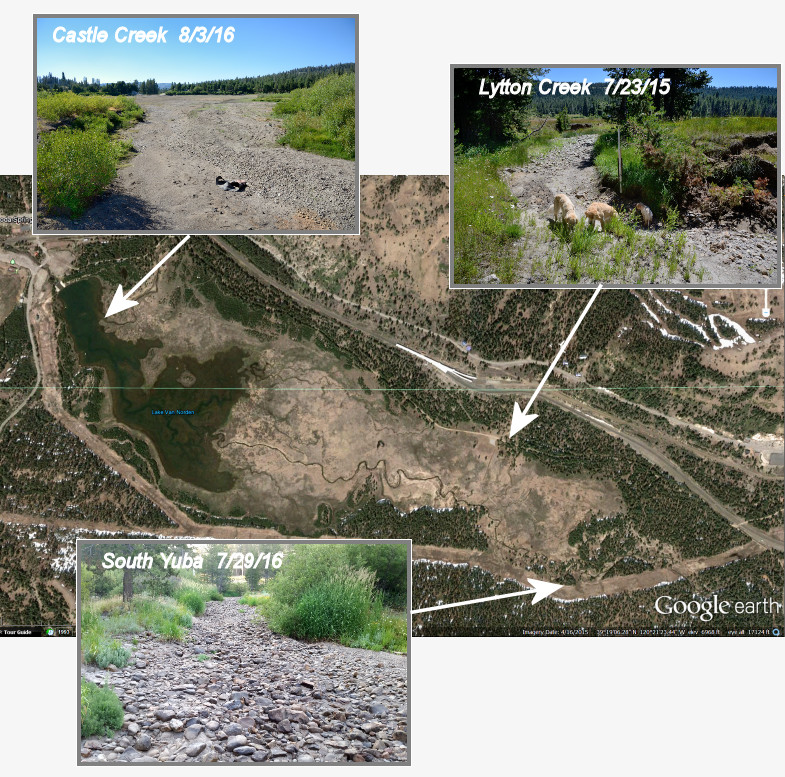

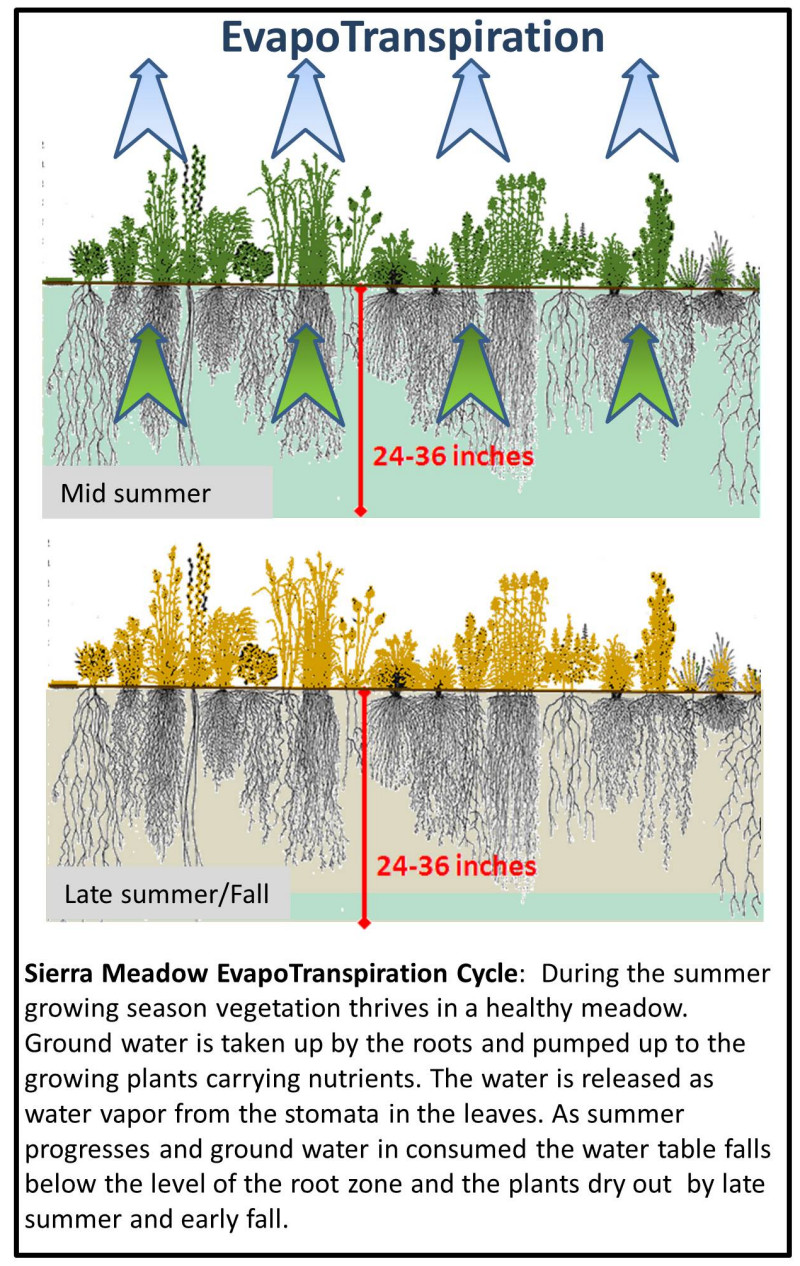

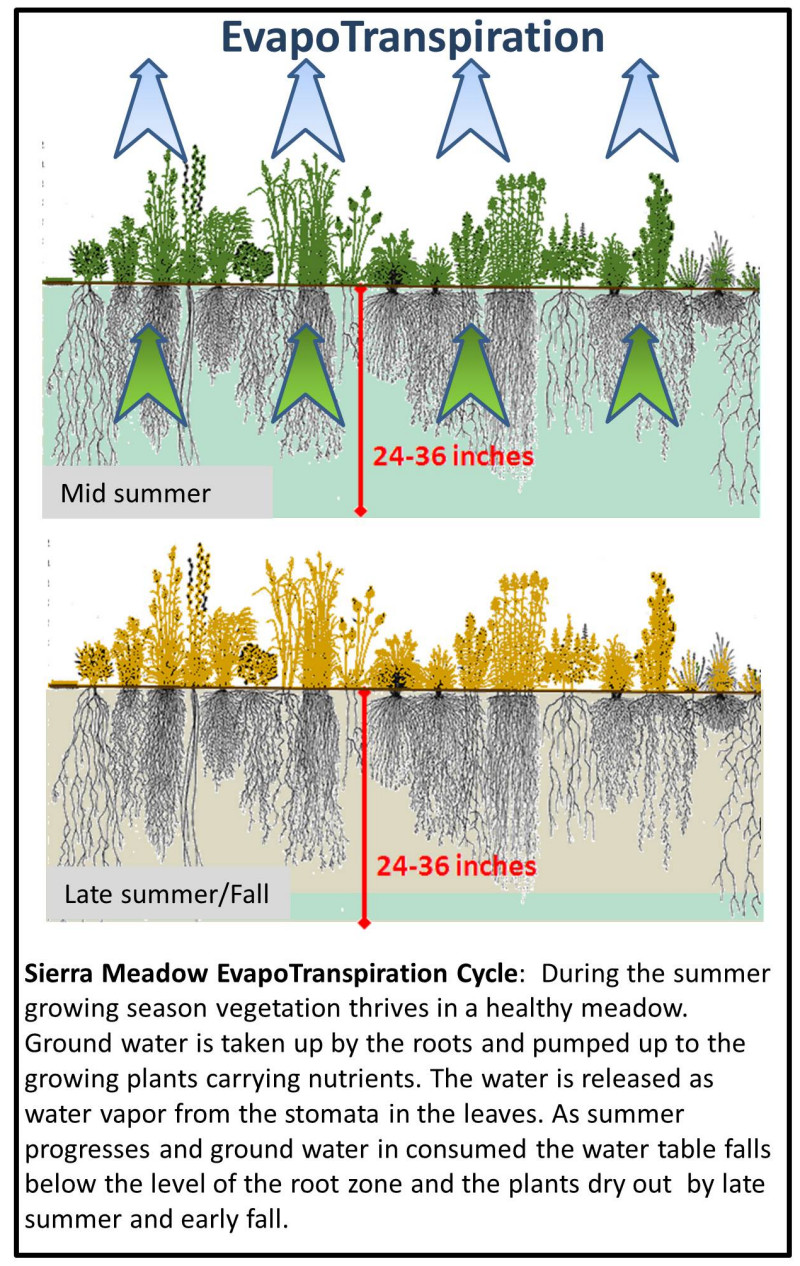

Up until this time in the cycle the major loss of water from the valley has been the natural drainage down the South Yuba River. Once that stops in mid summer (see this post) there is another natural process that becomes the major loss of water from the valley, evapotranspiration (ET). ET is the process that operates in plants in which water infuses into the roots of a plant and then is pumped up to carry nutrients up into the growing plant. Because the flow is primarily in one direction, the excess water is pumped out of the plants via openings called stomata on the leaves and stems. Once all the surface water has drained, a meadow becomes a battleground for all of the wonderful grasses, sedges, willows, trees and wildflowers that all try to suck water out of the soil to grow, flower and spread their seeds. As any farmer knows, it is the ET of their crops that is a major factor in how much water they need to irrigate with to bring in a harvest. ET completely breaks the sponge metaphor because it wrings the sponge dry so that by the middle of September all the ground water has been pumped out of the valley by the plant life which again goes dormant for another year when the ground water level drops below the typical root depth of 3-4 ft. This is when the Summit Valley turns to gold as the grasses dry out.

Water Storage

The first settlers in the Donner Summit area quickly learned about the natural water cycle of the Summit Valley. They realized that if they wanted to keep some water in the valley to last through summer they would have to dam the Yuba. As early as 1870 (just 25 years after the first pioneers passed through the valley) the first dam in the valley was being constructed. From that time until this, there has been a dam on the Yuba to store water in the valley during the dry summer and fall months.

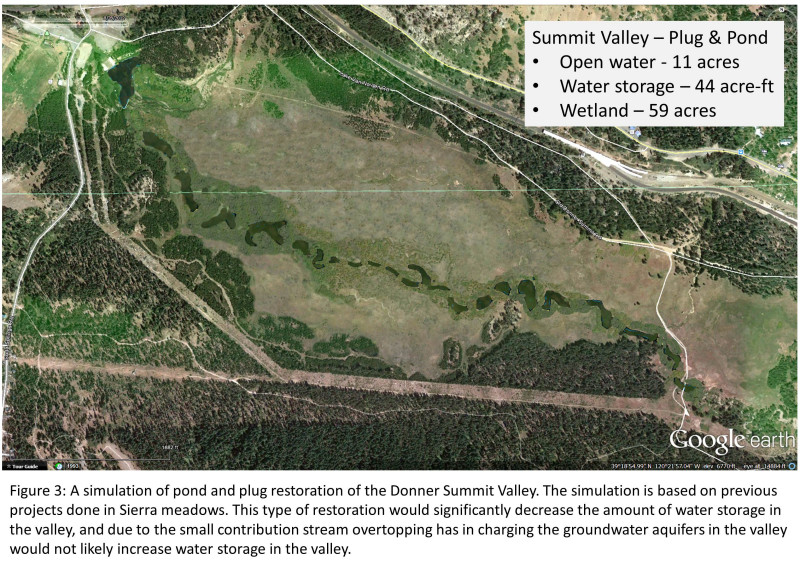

So getting back to our absurd assertion, the Land Trust would have you believe that the current 180 acre-ft of water stored in Van Norden Lake can be replaced and even increased by draining the water and replacing it with meadow. This bit of hocus pocus will be done by “restoring” the meadow which will supposedly increase the overall ground water storage in the valley using methods such as pond and plug.

Here is why this just doesn’t work:

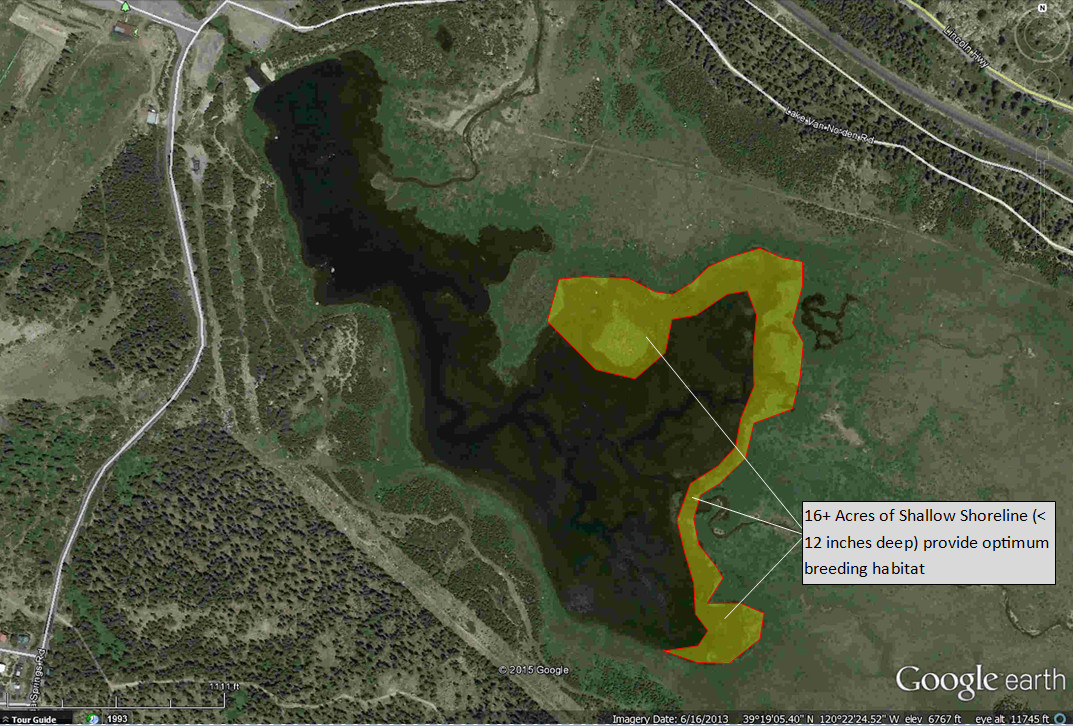

- Currently the lake stores 180 acre feet of water and covers 70 acres of land that stays completely saturated during the summer. The lake is in fact the flood that is connected to the floodplain. Not only will the 180 acre-ft of water be lost, but the 70 acres of new meadow will no longer remain saturated during the summer and will be actively pumping water out of the valley via the ET process. Open water lakes where simple surface evaporation is at work are much more efficient at storing water than meadow where ground water is actively being pumped out by vegetation.

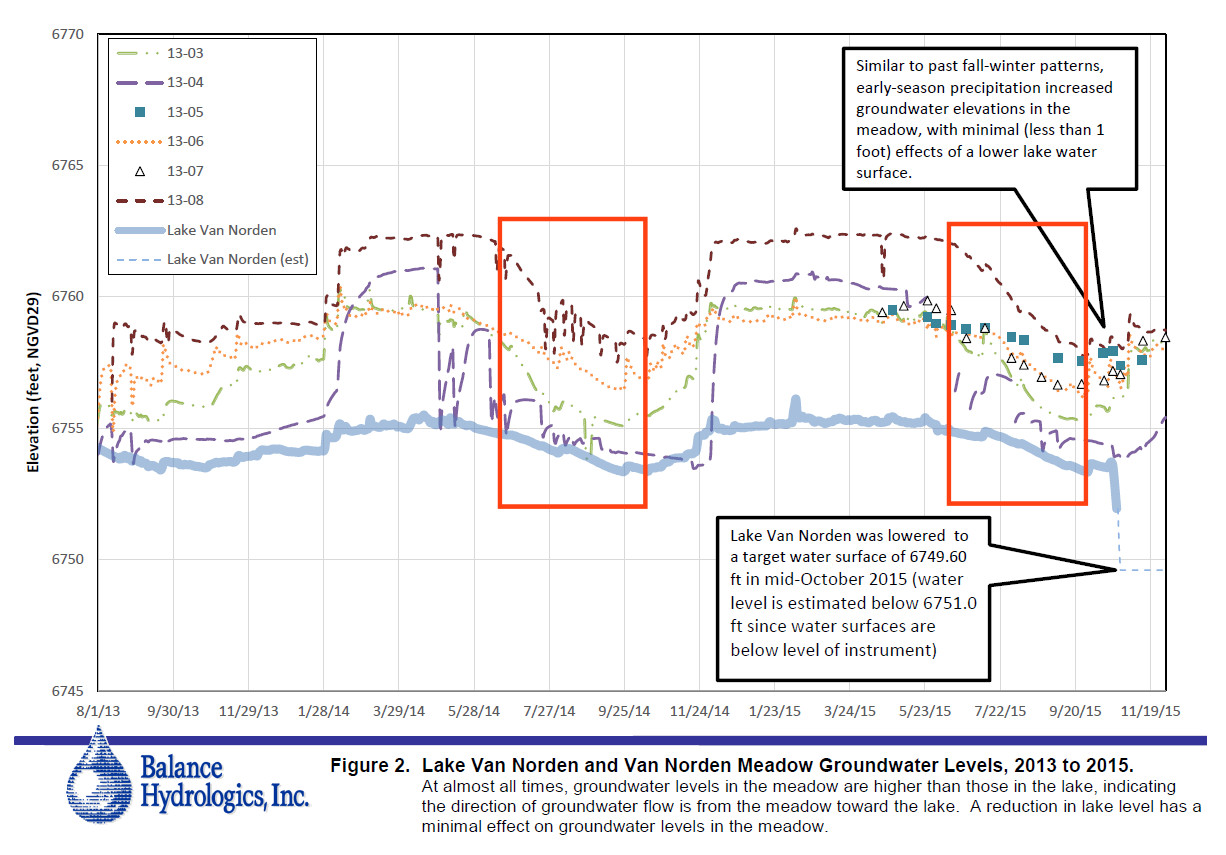

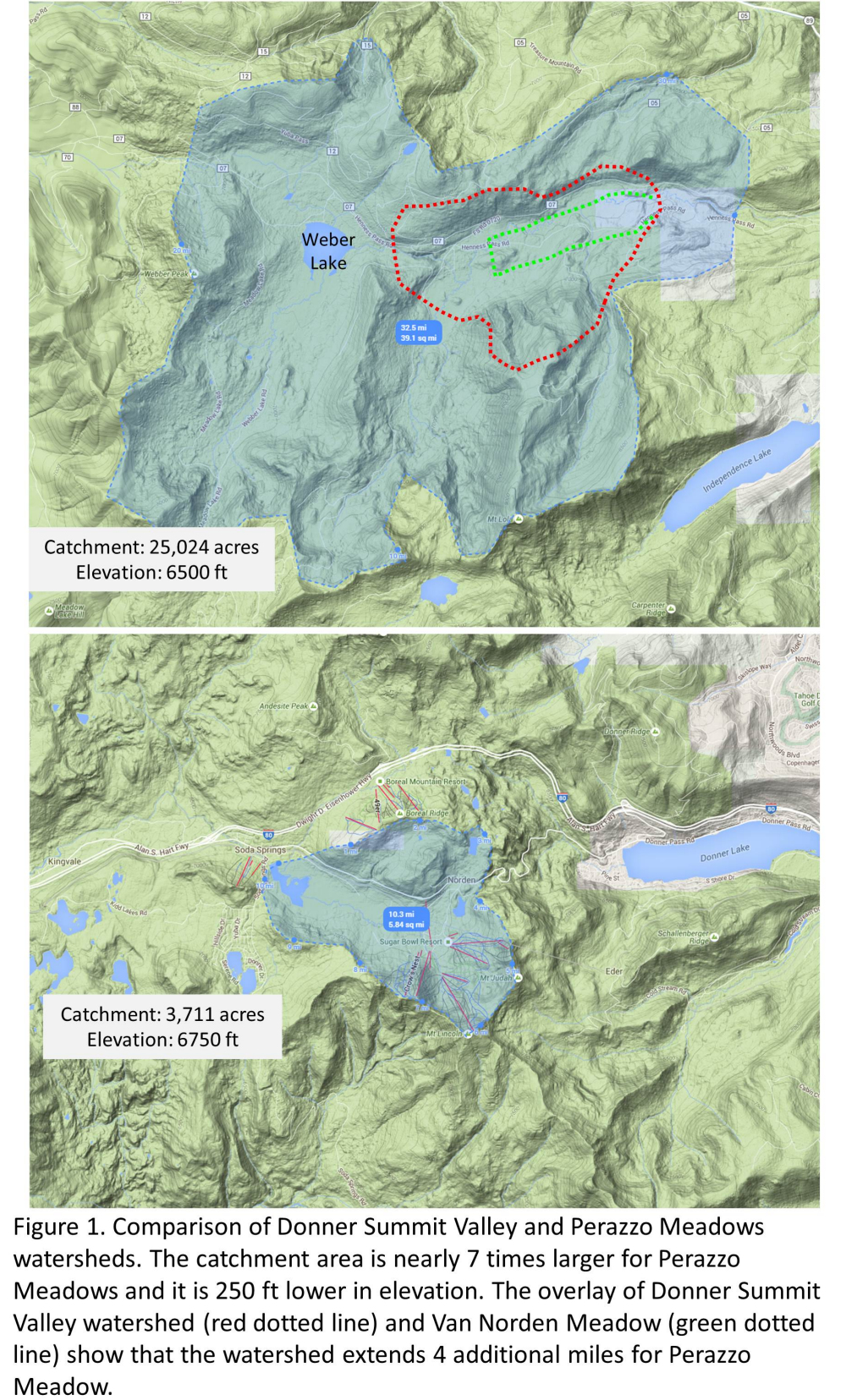

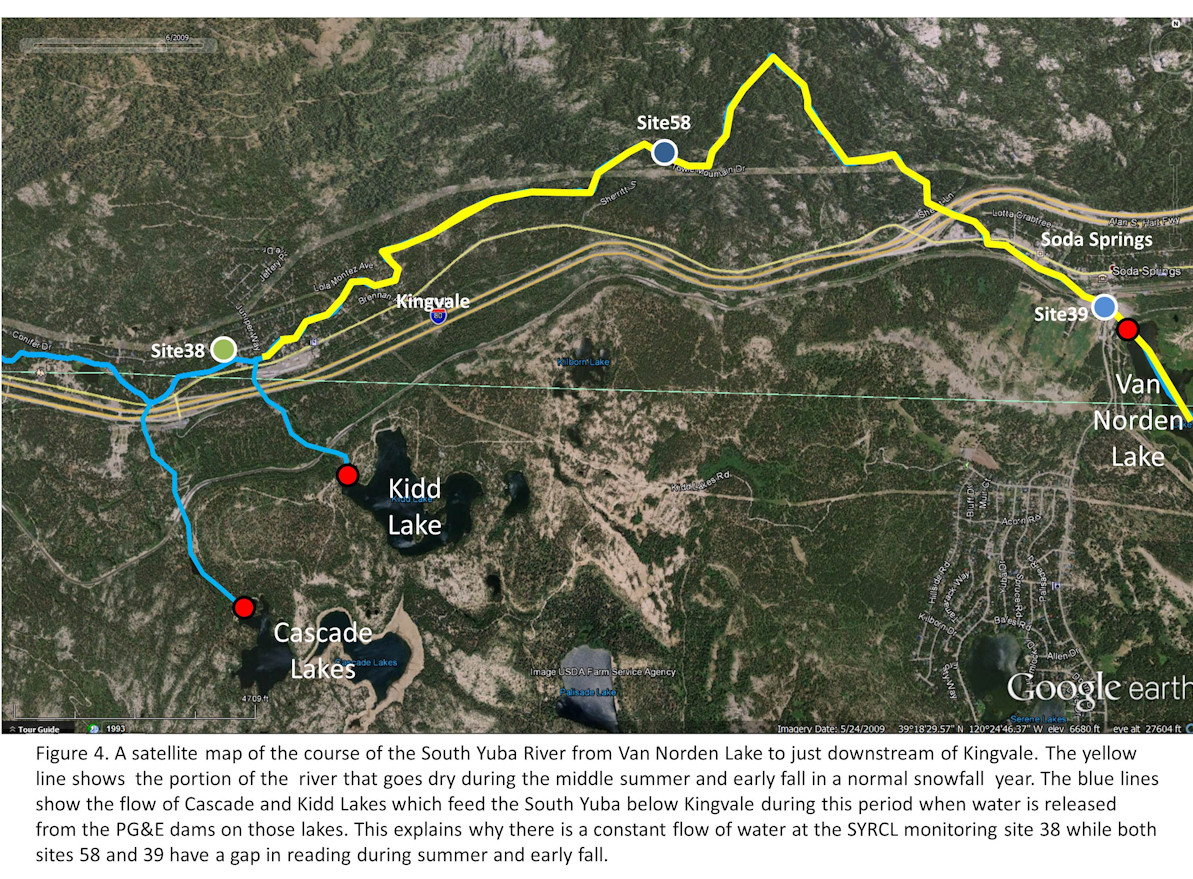

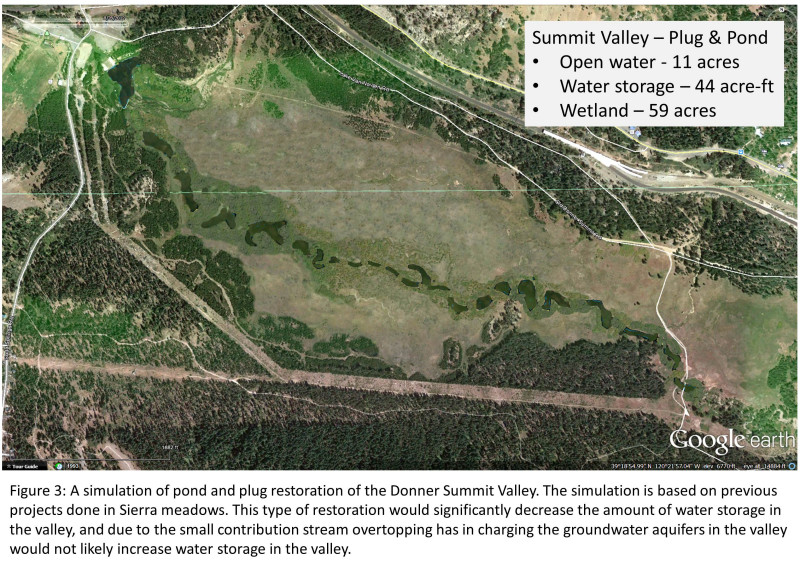

- The pond and plug technique can only reconnect the floodplain when there is a constant source of water coming into a meadow to keep the water overtopping the banks of the ponds. This works well with transitory meadows being fed by upstream flows. I a situation where a transitory meadow has been disconnected from the creek flow, reconnecting the flow via pond and plug can increase storage in the meadow by recharging the groundwater. This is not the case for a headwater meadow like Donner Summit Valley where there is no upstream flow. The Donner Summit Valley remains inundated well into July due to snow melt drainage from the meadow and surrounding mountains. To increase the length of time the ground water aquifer would remain charged using a pond and plug restoration, there would have to be a continuous flow of water from the Yuba to keep the ponds overtopping their banks. Unfortunately, there is no more upstream input into the meadow after July (see this post) because the watershed has drained (see Figure 3).

- While there may be some added storage of open water at the east end of the Summit Valley with the installation of small ponds and plugs, this water will be a small fraction of what will be lost when the lake is drained at the west end of the valley (see Figure 3). Moreover, as summer progresses, the small amount of residual water in the ponds will be reduced by ET from the surrounding vegetation without replenishment from upstream.

The bottom line is that your common sense intuition is correct. Removing the Van Norden Lake from the Donner Summit Valley will significantly decrease the amount of water storage in the valley. Trying to apply concepts of meadow restoration that don’t really apply to a headwater meadow like the Summit Valley is misguided at best. Asserting that there will be more water storage without the lake is ABSURD.

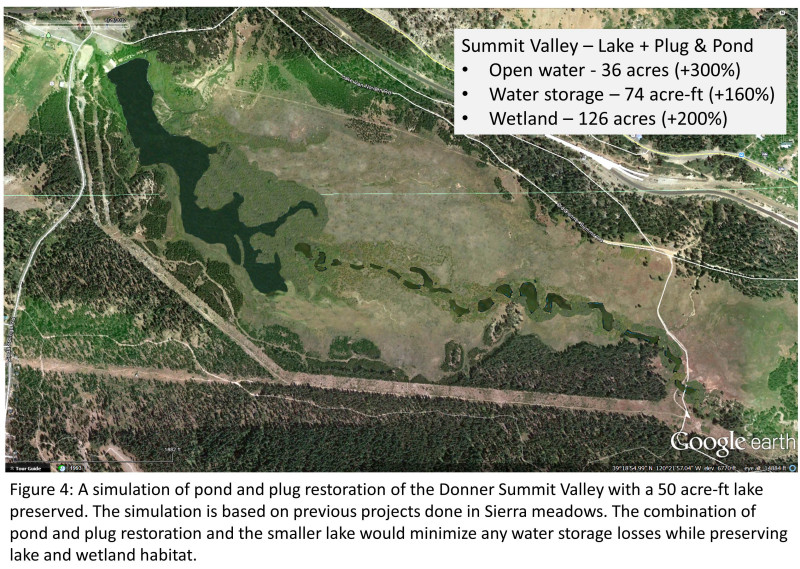

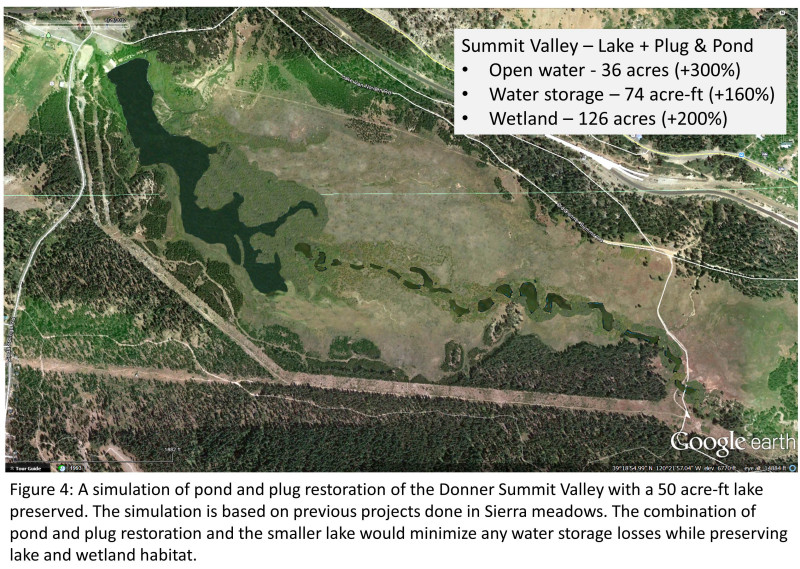

If the Truckee Donner Land Trust really wanted to maintain water storage in the Donner Summit Valley, we would encourage them to adopt our compromise plan that would maintain a 50 acre-ft lake in the valley. If they combined their meadow restoration plans with the retention of a small lake, they would minimize the amount of water storage loss due to the reduction of the current lake. At the same time they would be preserving the lake and wetlands habitats that add rich biodiversity to the Summit Valley. A win, win!